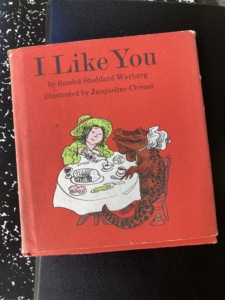

Women are storytellers and consciously or unconsciously constantly use stories to communicate. We navigate life telling, remembering, and listening to stories. The key is to be conscious and to honor this powerful ability within ourselves. For how many thousands of years have women told stories to children before they sleep, or used stories to explain a moral rule or household habit? We know the stories of our community, and we are often entrusted, whether we like it or not, to be the holder of family secrets. We find it easy to contain and hold and tell the stories of those we know and love. More complicated, for reasons that I will explore in the coming pages, is putting ourselves both literally and metaphorically as the central protagonist in our own grand story called Life. When we center ourselves as characters in our story, the one that we live and write, we validate ourselves. Writing our story, what happened and what we felt about what happened, is one of the most powerful ways that women can define, heal, and reckon with ourselves.

A divorce story forces us to center ourselves within the context of our own life. Willingly or unwillingly, we as women have frequently been assigned roles that have translated into prioritizing others needs before our own. By default and extension, we become reluctant to claim a space for ourselves, and in turn, the best we can often muster up, is to claim a segment of others’ stories for our own. While any story has many characters, we can do this to the point where we forget our story, downplay our role in others’ stories, deprive another of their own story to live to satisfy the absence of our own story, and most tragically, and all too common, think that we never had a story, or that our story was secondary to another’s because such a person received more external validation in terms of money or status.

Women are almost always rewarded for compliance, for putting others first every step of their lives and are bestowed praise for living the accepted narrative of a helpmate to everyone within a world governed by men. Our names change upon marriage. We are not on stage; we are Stage Mothers. Our salaries our lower. Our hours are longer. We are the stop gap go-to person for when all systems fail, when a family’s in crisis, a car malfunctions, a child is sick, or when someone is laid off. Everyone turns to us for caregiving. The status quo rewards us for making our story shorter, for functioning solely as a prelude to the stories labeled more significant, even if they are the stories of our loved ones. We almost always define ourselves in relation to another person and if we fail to do this according to an imagined bar of sacrifice and service, we feel poorly about ourselves or others judge as inferior or lesser. There is a huge difference between living a story that exemplifies love, loyalty, and kindness, and being measured as worthy because of what compromises one has made to exist in a relationship with another.

Divorce is often the first time we may consider the real depth of our individuality. We may have always told the story of our marriages, relationships, romance, and families with the royal plural “We” as opposed to the humble first person “I”. This is how writing a divorce story can empower: if we were firmly entrenched in the “we” of being a couple, becoming the main character of the story is a shock to the system! There are a minimum of three stories in every marriage. The “I” story of each individual and the the “We” story they mutually narrate about their coupledom. It is vitally important to state that our lives do not exist in a vacuum, and that we are deeply affected and directed by the culture of our time.

Once we recount the story of what happened in our marriage and what we felt about what happened, we can boldly claim space in a new arena. The story of a public life almost always sets the man’s story as first, the woman’s story as secondary. As women, the divorce story we share with honesty, is the story of the marriage wholly from our personal perspective. Know that writing this personal story solely from our own hearts is not an act of selfishness, but an act of personal volition. It is saying to the world: My story is worth telling because I have value.